Geophysics - Gravity Models

Introduction

My previous post that began this series of articles on surveys introduced the idea of solving the gravity response of a sphere mathematically and how this is well within the capability of detecting geologic anomalies below the surface with instruments. In this article we will take a deeper look into how we can reason about the physical phenomenon of a gravity response and using this to model simple geometric objects.

How does it work

The simplest geometry is a point mass, which you could visualize as a very small sphere. The gravity effect of this mass at another position is simply $g_r = G*m/r^2$. The direction of the effect is along the line joining the point mass and the observation point.

Gravity surveys are mostly interested in the vertical component of the gravity effect. This is what we can measure directly with a gravity meter that is calibrated and leveled. Therefore, we adjust the equation to determine just the vertical component.

$$ g_z = {G*m \over r^2} * cos(\theta)$$where $cos(\theta) = z/r, \ and \ r = (x^2 + z^2)^ {1/2}$

Combining, we get

$$ g_z = {G*m*z \over (x^2+z^2)^{3/2}} $$This is exactly what we get for a spherical mass with a non-zero radius a, density 𝜌, and volume ${4 \over 3}\pi a^3$.

As we saw in the previous post, the vertical gravity response of a buried sphere is:

$$ g_z = \frac{4\pi \gamma \rho a^3 z}{3(x^2 + z^2)^{3/2}}$$The only difference between the two equations is that the point mass has been replaced by the volume equation for a sphere and its material density.

Numerical Example

Units and powers of 10 are a confusing issue and needs to be addressed right here and now! I struggled with this for a time in order to get my computer programs to work correctly. The textbooks gloss over this because they were generally written when you needed to do the calculations by hand or with a calculator at most. I’m going to try and explain this and then we’ll see an example program written in Python. 🧐

The above equation is standard but what units do we use for a real calculaton? Without specifying the units of any of the terms, and using the default metric units, then g would be in $m/s^2$. That sounds pretty obvious, but let’s dig a little deeper.

Find the expected gravity profile for a sphere using the following parameters:

- gravitational constant, G = 6.6743 * 10^{11} {m^3\over kg.s^2}$ (see NIST)

- $\gamma = 0.0066743$ is often used to represent the gravitational constant, but this only applies when the density is 1.0 instead of 1000 kg/m^3, and the final unit for g is mGals, not m/s^s

- radius, a = 100 m

- buried depth below surface to centre of sphere, z = 500 m

- profile runs from -1000 m to +1000 m, at intervals of 50 m

- density differential of sphere with surrounding rock, 𝜌 = 1000 kg/m^3

Aside Let’s check our units:

We know that the acceleration due to gravity on Earth is $9.8 m/s^2$, but how do we know this? For most of us it’s because that’s what our teachers told us. Let’s not trust an unverified source. We can figure this out ourselves. But first we need some more data. A good source for the kind of data we need is the Earth Fact Sheet from NASA.

We can treat the entire earth as a sphere. We are standing on the surface and we are the gravity measurement device, we jump up and down, and confirm there is acceleration due to gravity. Let’s calculate it. We whip out our basic equation: $ g_r = {G * m \over r^2} $

- G = 6.6743e-11 m3/kg.s2

- Earth mass, m = 5.9722e+24 kg

- Earth radius at the poles, Rp = 6,356,752 m

- Earth radius at the equator, Re = 6,378,137 m

Do we need to worry about x. There was an x in the equation for a buried sphere. That was the horizontal distance of P away from the vertical above the sphere centre. If you think about it, any point on the surface is pretty much in line with the vertical above the centre. It’s not strictly true but the errors, for now, are very small. No, we don’t need x. (Why is this? The Earth is not a perfect sphere, and the density is not homogeneous, so the centre of mass is not at the geometric centre).

So, using the basic equation, g (at the equator) = 9.798 m/s2, and g (at the poles) = 9.864 m/s2. Well, that’s pretty close to what our teachers told us, so we just confirmed it.

Getting back to our numerical example, we repeat this calculation but we use the buried sphere equation this time. We loop through all our positions of P grabbing the right value for x from -1000 m to +1000 m in increments of 50 m. We calculate g, create a table of x,g pairs and plot the profile.

We need to look at one more unit. Normal units of gravitational acceleration are $m/s^2$. In order to work in units of mGal, we have to convert from $m/s^2$ to mGal by multiplying by a factor of $10^5$. How do we get this: 1000 mGal = 1 Gal = 1 cm/s2 = 0.01 m/s2, therefore 1 mGal = $10^{-5} m/s^2$.

You can use a spreadsheet to do these calculations, or you can write a program to generate the table and even a profile plot.

Sphere Modelling using Python

Code Analysis

- Lines 1,2: Import numpy and matplotlib.pyplot, fast math functions and a nice plot.

- Lines 4-12: Define the function to compute the gravity response at each x using the input values and closed-form solution. The function returns an array of solution values.

- Lines 15-23: Define the problem input values.

- Line 26: Use the defined function to compute the array of gravity values.

- Lines 29-30: List the table of x,g values to the screen.

- Lines 33-39: Use pyplot to generate a profile image of the x,g values.

|

|

> python3 sphere.py

x = -1000 m, Gz = 0.0100 mGal

x = -950 m, Gz = 0.0113 mGal

x = -900 m, Gz = 0.0128 mGal

...

x = -100 m, Gz = 0.1054 mGal

x = -50 m, Gz = 0.1102 mGal

x = 0 m, Gz = 0.1118 mGal

x = 50 m, Gz = 0.1102 mGal

x = 100 m, Gz = 0.1054 mGal

...

x = 900 m, Gz = 0.0128 mGal

x = 950 m, Gz = 0.0113 mGal

x = 1000 m, Gz = 0.0100 mGal

Vertical Cylinder Example

Now dig up the sphere and replace it with a solid vertical cylinder of equal density. This time the depth z is measured to the top of the cylinder, the radius is R, and its length is L. There is no closed form solution for the vertical gravity response of a vertical cylinder. A solution is possible using spherical harmonics and Legendre polynomial expansion, but I won’t go into it. Another solution is possible using numerical integration, which I will show in order to generate a profile similar to the sphere object. There is a closed form equation for the maximum gravity response which occurs at point P(x,y) = 0,0 or when the observation point is directly above the vertical axis of the cylinder. This is covered in Telford, p37-39. The equation is

when z,R,L are in meters, and $ 2\pi\gamma $ simplifies to 0.0419.

So, using values z = 500 m, R = 100 m, L = 187 m, we get 0.112 mGal, which approximates the maximum response for the sphere. You’ll notice that more mass is higher up (closer to the observation point) and the vertical length of the cylinder is shorter than the sphere. Also, the cylinder is 40% more massive, but the centre of mass is at a lower depth of 593 m.

This is one of the key points involving potential fields: a mass will produce a unique gravity potential field, but a potential field alone does not predict a unique mass, nor how it is spacially distributed.

A closer look at this equation highlights some special cases:

-

If $ R \rightarrow \infty $, the cylinder becomes a horizontal plate of infinite extent and

$$ g = 2 \pi \gamma \rho L $$This is the

Bouguer correctionterm, which I will describe in a later post. -

A method of computing

$$ g_t = \gamma\rho\theta\big[ (r_2-r_1) + \sqrt{r_1^2+L^2} - \sqrt{r_2^2 + L^2}\big] $$terrain correctionsbased on sectors of a ring (Hammer Charts), is derived from the development of this equation. The result iswhere $ \theta $ = a sector in radians. I will describe terrain corrections in more detail later as well.

-

When $ z=0 $ , the cylinder outcrops at the surface and we get

$$ g = 2\pi\gamma\rho\ [L+R-\sqrt{L^2+R^2}]$$ -

If $ L \rightarrow \infty $, then

$$ g=2\pi\gamma\rho\ [\sqrt{z^2+R^2}-z] $$and if at the same time $ z = 0 $, then

$$ g=2\pi\gamma\rho R $$

Solving the Vertical Cylinder Gravity Response using Numerical Integration

We know how the basic law of gravitation behaves. The gravitational force is a vector whose direction is along the line joining the centres of the two masses. This is only strictly true when they happen to be point masses. If we consider a 3-dimensional mass of arbitrary shape, a blob, like a typical asteroid, then the gravitational potential or response at a point away from the mass can be found by dividing the entire mass into smaller chunks, calculating the response of each chunk, and summing to get the total response. Since the mass is the volume * density, and the volume and distance are functions of the x, y, and z geometry, we can write the gravity response like so

Nothing too scarey, right? Ok, let’s break it down. We will not be integrating, instead we will turn this into a discretized model where the tiny element has dimensions $\Delta x, \Delta y, \Delta z$. Since the total mass is a circular cylinder, we won’t be using the usual x-y-z coordinate system. For this problem, we will go with cylindrical coordinates $r,\theta,\ell$. So rewriting the equation, we have

$ g = G\rho \int_x \int_y \int_z{V(x,y,z)\over d(x,y,z)^2} = G\rho \sum_\theta \sum_r \sum_\ell {V(\theta,r,\ell)\over d(\theta,r,\ell)^2}$ where a small element $\Delta V = r \Delta \theta \Delta r \Delta \ell$, and d is the distance between the small element and an observation point P.

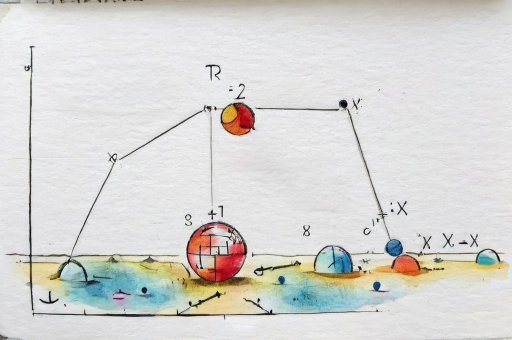

The notation still looks scarey, so lets look at the diagram below.

Imagine the cylinder is made up of discretized elements, one of which is coloured red to show it singled out. We are going to choose the order of the summation to go $\ell, r, \theta$ for efficiency reasons, but any order will work. Looping through $\ell$, while the other variables remain fixed, you can visualize the red element starting a the top of the cylinder and moving to the bottom of the cylinder. Then we move along the radius a distance of $\Delta r$, keeping $\theta$ constant still, and running the element from top to bottom again. When all of the columns of elements along one radial line is complete, we move the radial line over by $\Delta \theta$ and do it all again, and again, all around the circle.

$$g = G\rho \sum_{\theta=0}^{2\pi} \sum_{r=0}^{R} \sum_{\ell=D}^{D+L} {\Delta V \over d^2}$$

Code Analysis

- Lines 4,5: Import numpy and matplotlib.pyplot, fast math functions and a nice plot.

- Lines 7-16: Define the problem input values.

- Lines 18-46: Define the gravity response function - the heart of the program

- pass in the dimensions of the cylinder and the observation point, z = 0

- initialize the response sum, and increment values of $\theta,r,\ell$

- outer loop increments $\theta$ from $0 - 2\pi$, calculates $cos\theta, sin\theta$

- middle loop increments r from 0 - R at a constant $\theta$, calculates $\Delta V$ at r

- inner loop increments $\ell$ from D to D+L

- we can finally calculate the distance d between point P and the tiny element

- line 44: we are only interested in the $g_z$ component of the full response

- line 45: we finally compute $\Delta V cos(\phi)/d^2$ and accumulate the result

- when all the loops are done, return the $\sum g_z$ for point P

- Lines 48-50: Function to convert m/s2 to mGals.

- Lines 55-60: Loop thru the x values and compute the gravity response at each x.

- Lines 62-65: List the table of x,g values to the screen.

- Lines 67-74: Use pyplot to generate a profile image of the x,g values.

|

|

The input parameters were slightly different for this run:

- the cylinder length is 1000 meters

- the profile is a bit longer: -1500 to +1500 meters

- everything else is the same

Using the same equation above for $g_{max}$, we find $g_{max} = 0.2756 \ mGals$

This should match the value at x = 0 in the table, which it does with an error < 0.6%

I think this is pretty good, if we consider how many tiny elements were used in each summation.

Notes on Program Runtime: unfortunately, the runtime for this program was pretty bad, taking 37 minutes on an M1 iMac. It computed the response for 61 points, taking more than 30 seconds per point.The number of elements is found from the limits of the 3 loops (ie summations) divided by the increment: $2\pi/0.02 * 100/1 * 1000/1 = 31,415,926$ elements

python3 vert-cyl-integ2.py

X (m) e Point 15 Gravitational Response (mGal)

-1500 0.0336

-1450 0.0360

-1400 0.0386

...

-200 0.2468

-150 0.2579

-100 0.2666

-50 0.2721

0 0.2740

50 0.2721

100 0.2667

150 0.2580

200 0.2468

...

1400 0.0386

1450 0.0360

1500 0.0336

Conclusions

You’ve now seen how we can start from first principles and develop some mathematical models to calculate the gravity response of simple geometric shapes. We can sometimes find a closed solution for a geometric shape, but when we can’t we can find numerical solutions or run discrete summation loops as with the vertical cylinder. Once we know how to work with basic geometric shapes, we can proceed to model more complex geology or use them to fit our observatons. Modelling normally involves building a cross sectional 2D or 3D model and iteratively adjusting it to reproduce the observed data. This is called the Direct or Forward modelling approach. However, it does not generate a unique model; other mass distributions can also produce the same set of field data. A project will undergo several different surveys and combine the results to aid in the final interpretation.